What is Balanced Audio?

Sometimes you’ll see the terms “balanced input” or “balanced output” when reading the specs on a piece of audio gear. What’s the difference, and why does it matter?

Put simply, a balanced signal is designed to carry very weak signals, often over very long cable runs, without picking up a lot of noise from nearby power amps, unshielded wall warts and other power supplies, mobile phones, Wi-Fi networks, and even solar flares.

While unbalanced wiring works fine for short cable runs in a home studio – and it’s the only way to connect an electric guitar to an amp – you won’t want to use it to send signals from a stage rig to a Front of House mixer, or from a studio microphone to your audio interface.

While there’s always a risk of noise from improper grounding (which can be addressed by isolation boxes such as Samson’s MLI1), bad cables, or other sources, the most common culprit is electromagnetic interference or EMI. When the interference occurs at radio frequencies, the common abbreviation is RFI.

Balanced wiring is specifically designed to reduce or eliminate EMI. Here’s how.

Interference of the Electromagnetic Kind

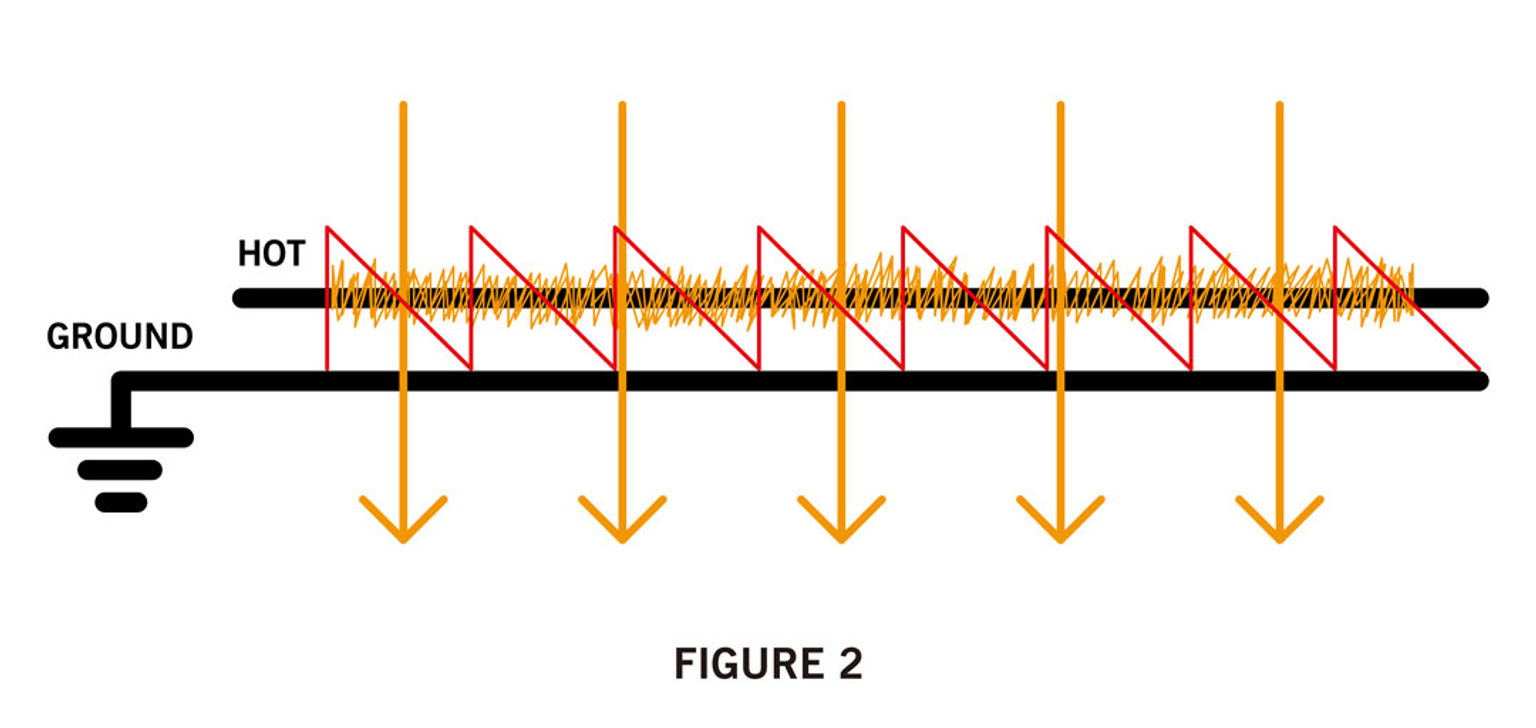

Without getting into a lot of physics, when an electromagnetic field passes through a cable, it acts like a transformer, setting up a corresponding field inside the cable. This effect is audible as an unwanted noise signal that’s mixed with your desired audio signal. While some plug-ins can try to isolate and remove this noise, using a balanced cable eliminates it before it ever gets to your gear.

A Careful Balancing Act

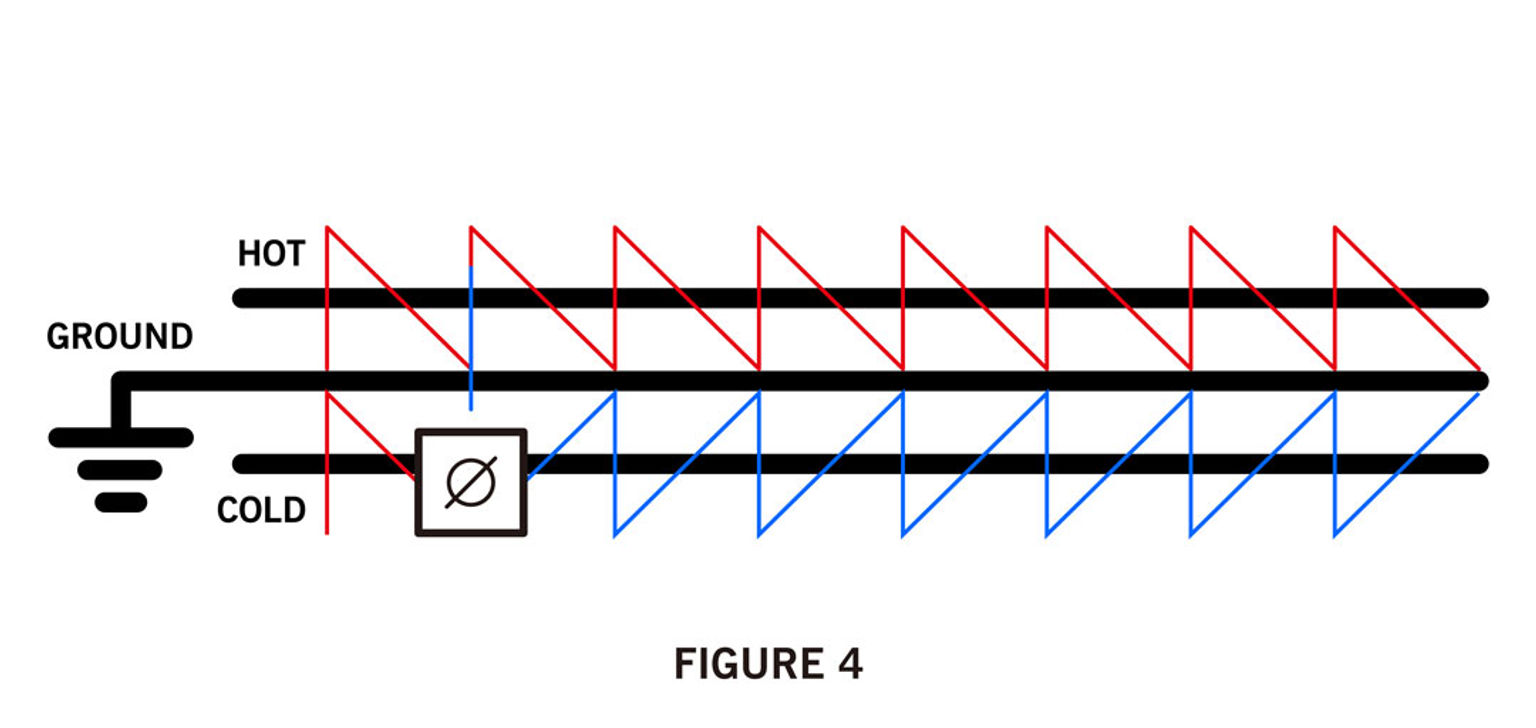

The term ‘balanced’ comes from the fact that there’s equal impedance at both ends of the cable. That means the signals on the hot and cold wires are exactly the same amplitude, which is very important, as we’ll see.

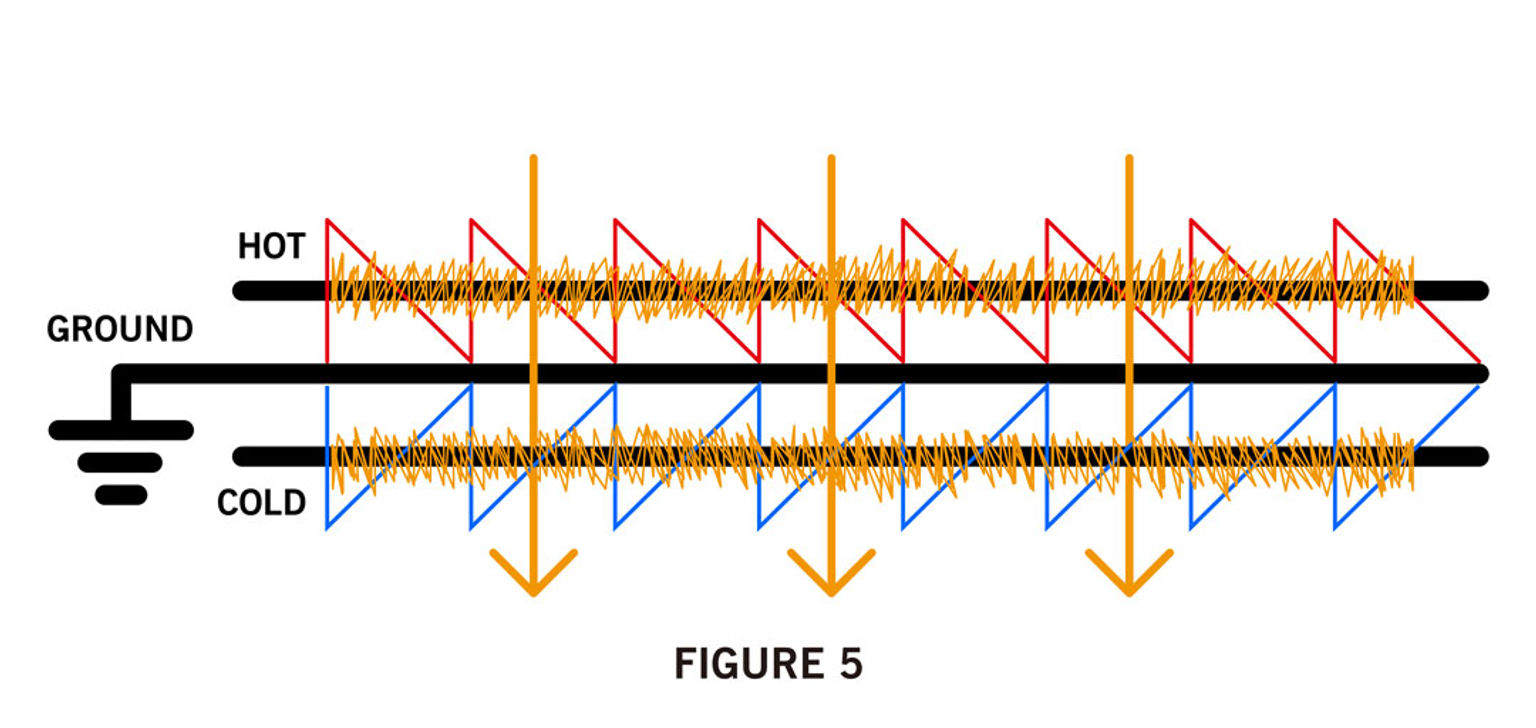

Notice how the noise is identical on both cables? That’s because the hot and cold wires are twisted closely together, so the EMI (which depends on distance from the noise source) has an equal effect on both, also an important factor.

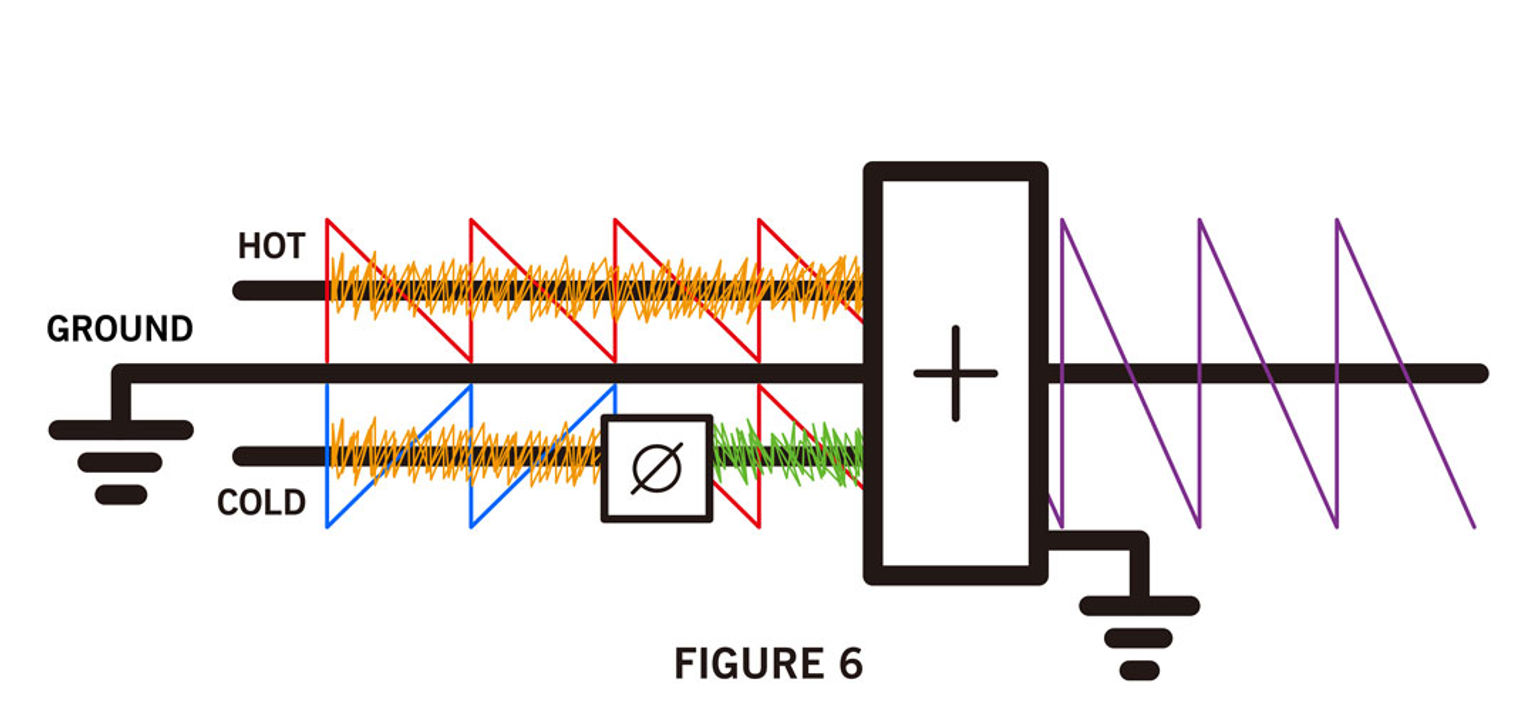

The hot and cold signals head down the line, each carrying its own noise. However, when the signals arrive at a balanced input, the signal on the cold wire is inverted again – which now inverts the noise as well – and added to the hot signal.

Where to find balanced audio connections

Manufacturers can decide to make connections balanced or unbalanced for a variety of reasons – sometimes they have to be one way or the other, other times it doesn’t matter. For example, while Samson MixPad mixers come with both balanced and unbalanced inputs and outputs, the MediaOne M30 powered studio monitors have unbalanced inputs, and direct boxes like the MD1 Pro, MDA1, and MCD2 Pro have unbalanced inputs and balanced outputs. (By the way, a direct box not only balances the audio signal, but it also changes signal impedance from high to low – an important task that we cover in another article.)

Know your plugs, know your pins

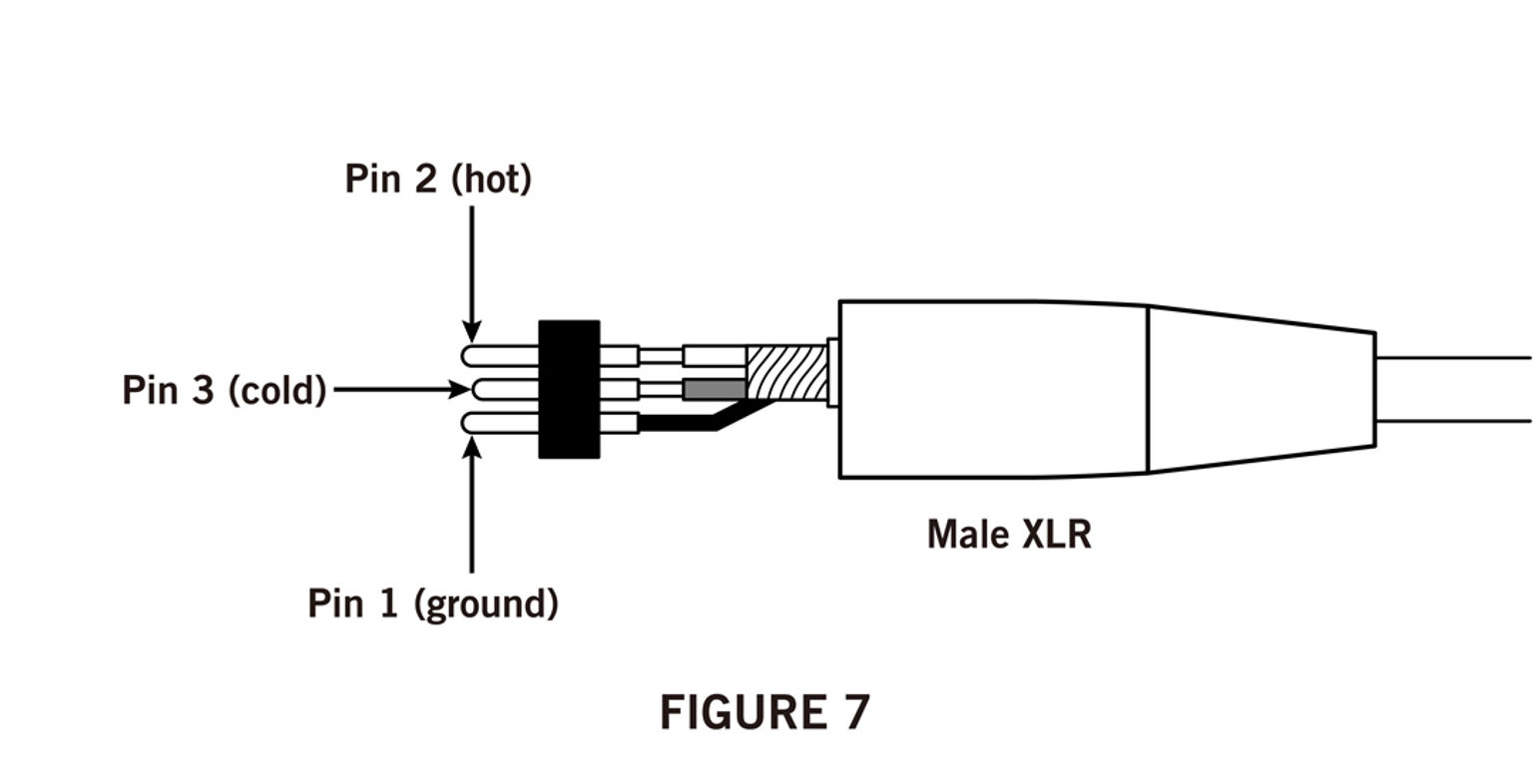

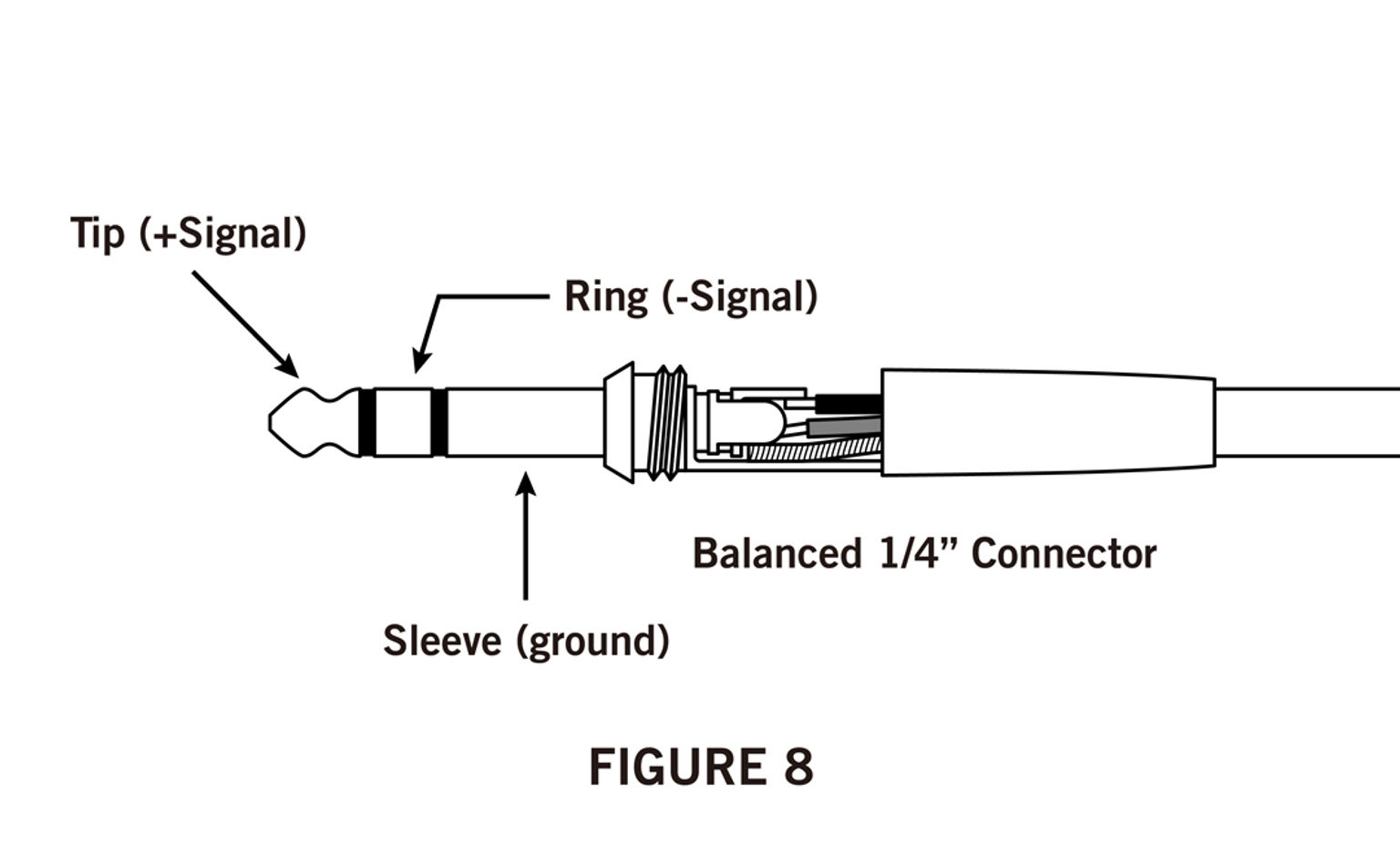

A plug with three connectors doesn’t always mean a balanced cable. Sometimes a TRS 1/4” cable is used to accept stereo signals and split them into two mono cables, with the left hot signal on one and the right hot signal on the other, both unbalanced. Similarly, when a mono unbalanced cable is connected to an XLR adapter, it doesn’t automatically become balanced. But by and large, when you see an XLR mic cable or a TRS-to-TRS 1/4” cable, it’s meant to carry balanced audio. See Figures 7 and 8 above for a couple of wiring examples.

One last note: in the very early days of audio gear that used balanced XLR connections, there was a dispute as to which of the three pins carried the hot vs. cold signals. Pin 1 is always the ground wire, and these days, nearly all gear uses Pin 2 hot and Pin 3 cold. However, there were a couple of manufacturers back in the day that used Pin 3 hot, so when working with vintage gear, it’s always a good idea to glance at the manual.

And that’s balanced audio – a handy way to get your signals where they’re going while making sure that noise doesn’t come along for the ride.